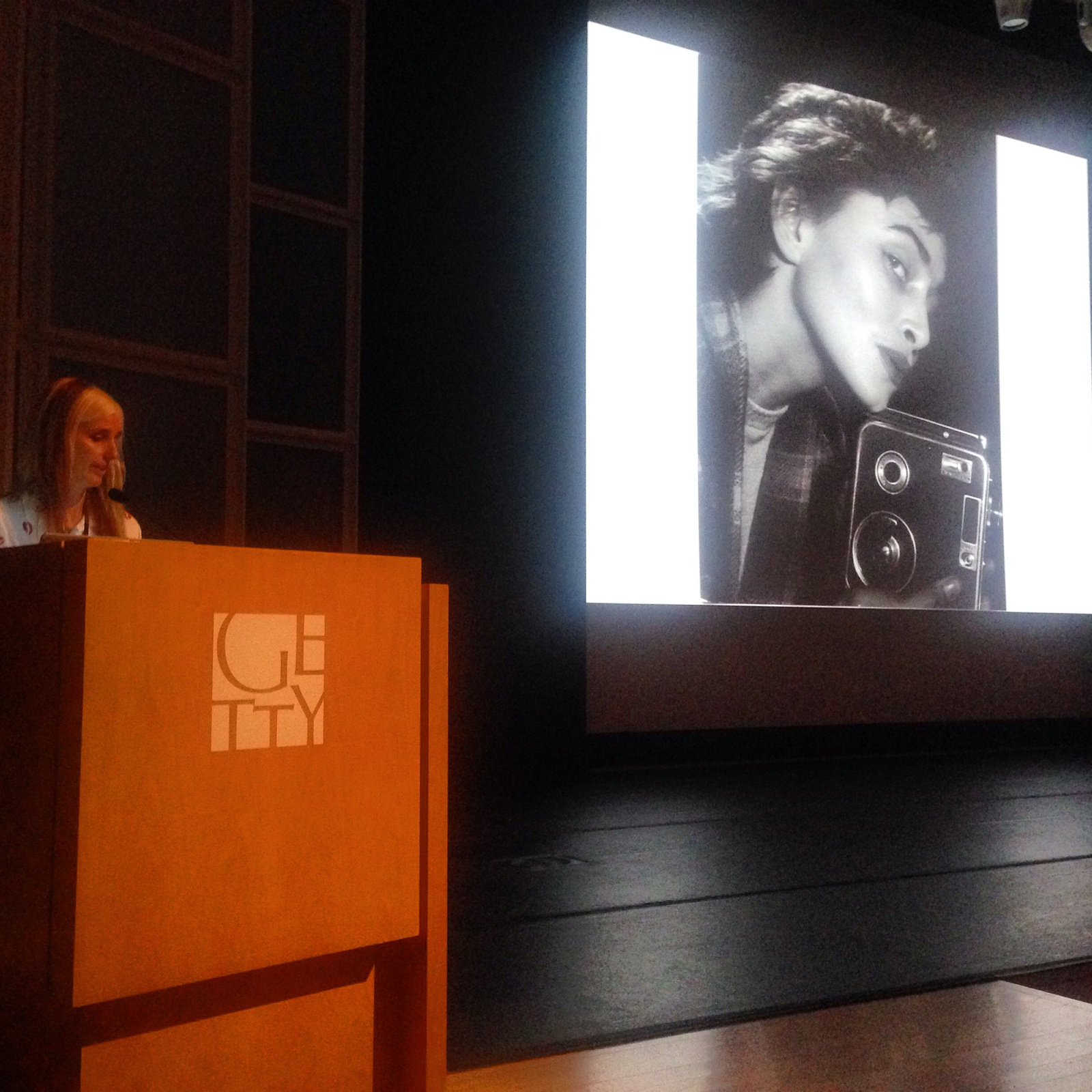

dir. Vera Chytilová, 35 mm screening

Introduced by Jennifer West

December 6, 2014

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Discovering “Daisies”

SARAH COOPER | NOVEMBER 26, 2014

Art Stories, Getty Iris Blog

Daisies, a mischievous film made in Prague in 1966, is the most dazzling experimental effort of the Czech New Wave. Its opening scene sets the delirious tone.

Two bikini-clad girls, one blonde and one brunette and both named Marie, sit propped up on a monochromatic pool deck like marionettes. Each stiff movement they make is bizarrely punctuated by the creak of an old wooden door. After a quick downward strike of a hand, the film flashes footage of a collapsing bombed-out building façade, apparently toppled over from the gust of this simple gesture. One Marie says to the other, “Everything’s going bad in this world.” They look at each other and decide, “Well, if everything’s going bad, then we’re going bad too!” In her first debaucherous act, one girl reaches out and slaps the other, who flails backward and transports out of the black-and-white sunbathing scene into a lush, radiantly colored meadow of daisies. The Maries fall through a rabbit hole to a new place where this kind of free-form absurd surrealism is everywhere—and they then misbehave their way through a cycle of kaleidoscopic scenes.

The film’s extraordinary director, Vera Chytilová, passed away this past March at the age of 85, and the Museum will be screening her masterpiece on December 7 in conjunction with the exhibition of fellow Czech artist Josef Koudelka. Chytilová made Daisies in collaboration with her husband, cinematography wizard Jaroslav Kučera, and Ester Krumbachová, an artist who infused the sets and script with her romantic, radical style. The Maries’ apartment was said to be based on Krumbachová’s own, with drawings, botanical illustrations, and images torn from magazines covering the walls. The anarchic film was banned by the Communist government, and Chytilová was effectively silenced, barred from working for nearly a decade.

I stumbled upon Daisies by chance at age 18. I was traveling to Baltimore from my hometown of Pittsburgh to meet up with a high school friend who had just started the foundation course at art school. That week, I followed her through a series of basement concerts, parties in artist’s studios and apartments, and bars we were too young to be in. I felt like I was getting a glimpse into a network of artists, young and old, who were constantly exchanging materials, records, and ideas. At one of these parties, there was a TV in the corner of a room with no one really watching it, and on the screen the two Maries were lunging at each other in a gleeful mania with scissors snapping away in each hand. Cut-out arms and heads free-floated across the screen as the scene dissolved into an elaborately mad collage. I only caught a few minutes, but it was like nothing I had seen before, and I knew I had to find out more.

When I got back to the decidedly less bohemian environment of the University of Pittsburgh, I started my search for this mysterious film. Because it was the late nineties, you couldn’t just find things online, and things still had that aura of being underground. After coming up empty at even the most indie video stores in town, I eventually contacted the Slovak Studies Department, who knew of someone who had brought films out of Czechoslovakia to Canada, and gave me his number. The abrupt person with a heavy accent said I was lucky, because Daisies was the only film he had with English subtitles.

A VHS tape arrived in the mail several weeks later, and after a few seconds of showing an empty room with white walls, the lights clicked off and you could hear the sound of someone flicking on a film projector. The film had been rudimentarily videotaped right off the wall! Clearly some proper videos were in limited circulation in some places, but I had this bizarre bootleg video tape that felt like it had a secret history.

I watched the film and knew I didn’t understand it, but also knew I loved it. It was overwhelming in its psychedelic color, esoteric sets, and cryptic dialogue, but that wasn’t its only impact. Rather, it was the ineffable sense that these things were powerful political and social messages, ones I couldn’t yet decode, that activated something new in me. It was completely weird, in a way that matched a kind of weirdness in myself. I forged a relationship of sorts with the film and have been thinking about it for more than a decade, trying to understand my connection to it and the world it came from.

At the time, the only thing I knew of Czechoslovakia was that my grandparents emigrated from there to Pittsburgh though Ellis Island as children at the turn of the century. My father grew up immersed in a Czechoslovak community that populated row houses perched along steep hills overlooking the blast furnace of Duquesne Steel Works, where my grandfather labored as a steel worker. My grandparents would pass away before I got to know them, and my father never talked much about his heritage. Several of his memories of that community connect to attending Orthodox Catholic mass, with churches’ ornate gilded and icon-laden altarpieces.

That imagery would become important for another member of Pittsburgh’s Czechoslovak community, Andy Warhol, who fashioned his own church of deviant and tragic icons. Chytilová, who was about the same age as my father and Warhol, grew up in a strict Catholic home in the town of Ostrava. She has said that while she left religion behind when she moved to Prague to become a filmmaker, those moral codes never left her.

Daisies reads as a morality farce, where the Maries find themselves as two Eves in a Garden of Eden, plucking a peach from the Tree of Knowledge instead of an apple. Beyond religion, Daisies seems to share a special affinity with Warhol’s ability to use hyper-real color and a sardonic aloofness to transform an innocuous image into a complex critique, which for Chytilová was distinctly feminist.

In my favorite scene, the Maries set fire to paper streamers and links of sausages dangling from wires on the ceiling of their apartment in an act both beautiful and insane. Lying around among the embers, they use enormous scissors to chop a whole array of phallic foods from pickles, sausages, bananas, and croissants until they run out. Still hungry, they turn to cutting out pictures of roasts from magazines and chew up the pages. In just one of the many moments in which Chytilová’s heroines toy with men, they eat their feast while ignoring the voice of a lovesick man who begs for their attention over the phone, then accidentally hang up on him when lying back with full bellies. Like Warhol’s bananas and soup cans, the ecstatic use of food, and its depiction in advertisements, becomes a political and sexual fascination, and the film’s climatic moment comes in the form of the epic destruction of a stately banquet.

My Daisies videotape became a personal talisman of sorts, and over time, it opened my mind to exploring an array of experimental art. It was those things I later learned about—Dada, Fluxus happenings, feminist performance art—that have in turn continued to unlock new aspects of the film for me.

Ester Krumbachová, who would lend her extraordinary and eccentric mix of earthy and occult style to several other films, notably the ominous coming-of-age vampire fairytale Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, is the underrecognized muse of the Czech New Wave. She too was barred from working under the Iron Curtain, but over the years she was known to have opened her wildly decorated Prague apartment to young artists, serving as a mentor and example of how to live an artistic life. Despite the suppression of her government, and even her death in 1995, the door to Ester’s apartment remains open though Daisies, and the curious happenings and constructions within it will continue to evolve with meaning for me, and all of us who are taken in by this film.